The Most Dangerous Thing About The Moment

Being too early versus too late, and how to lose the AI race as a founder and investor

It took all of 4? weeks for AI to enter the zeitgeist across a bunch of industries, forcing everyone from marketers to filmmakers to wonder if they were going to be obsolete in the coming years, and for investors to move from investing in dev tools/infra in AI/ML because the “space was early “to needing an “AI strategy” or an “AI person” with strong views on the application layer. We even got market maps!

What seems to have happened is that the demo culture we saw in a variety of other emerging industries (AR/VR, AVs) took hold and allowed a variety of people to not have to read academic papers or long blog posts, but instead see to believe. Even better, we no longer were forced to spin up an intimidating Colab notebook and instead got usable “demos” in Discord or simple UIs. The Curiosity Phase of AI was born and after 4+ hours of LLM demos at an AI event yesterday, it’s abundantly clear to many that the chasm between demos and products has been crossed.

Too Early vs. Too Late - The AI Wave

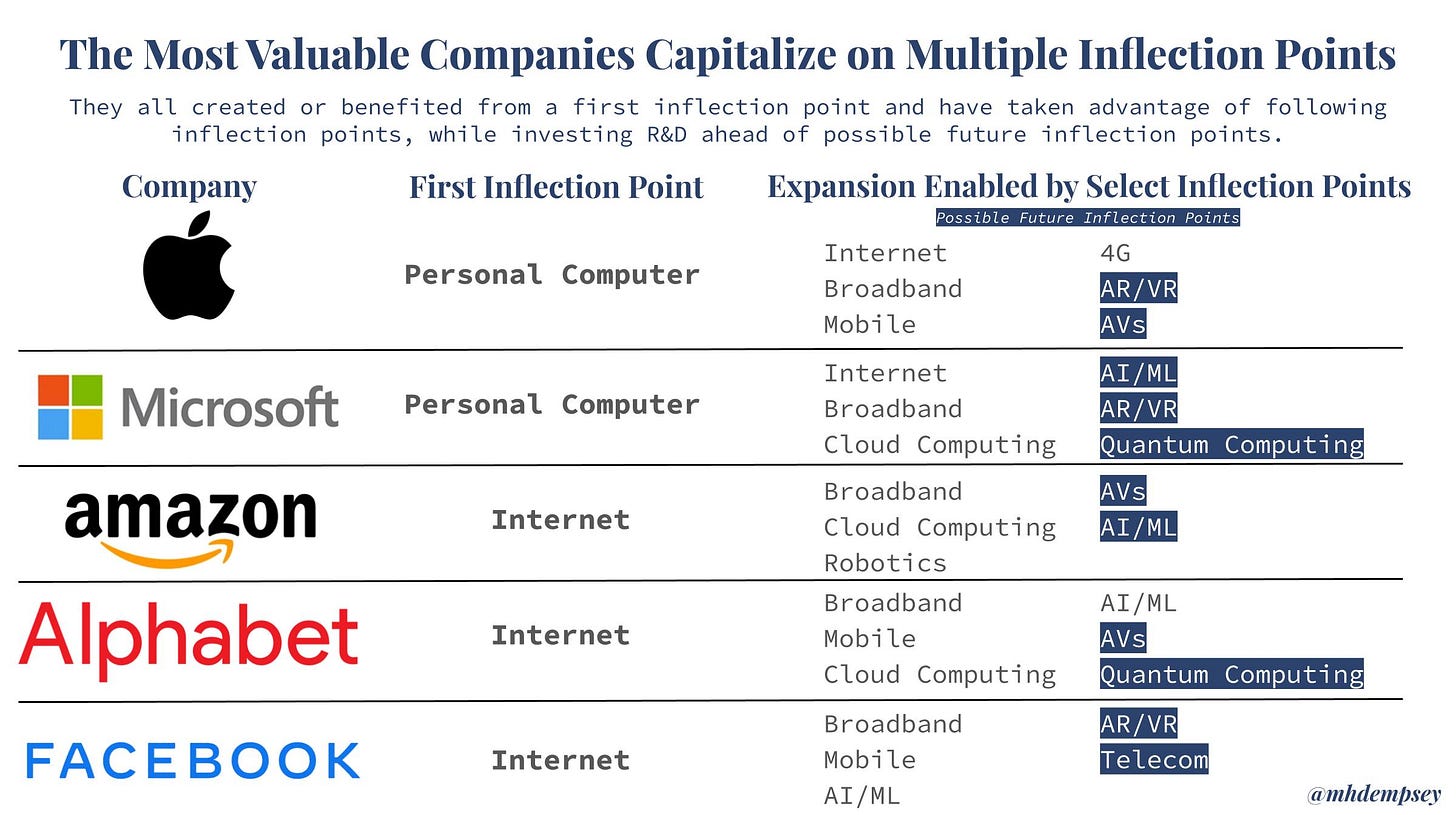

In 2016 I wrote a post titled “if you’re not too early, you’re too late” which made the argument that due to large balance sheets and R&D pace of incumbents, new entrants had to arrive to markets early and build ahead of the deployment phase, and that as investors, we must then be confident that we are backing companies that are “too early” historically. This “too early” stance meant investing was harder and a set of founders were being forced to thread the needle between science projects and mass market venture scale businesses. We continue to build our firm Compound around this viewpoint.

Recently Dino Becirovic made a similar point in his post “where are the next big waves” where he discussed this dynamic of needing to be “too early” and pushed forward the idea that venture potentially catalyzing markets meant that we could be headed for a lost decade of innovation.

In many ways, it feels like the abundance of capital has led to investors trying to catalyze nascent markets and bring them to the masses, in essence serving as outsourced R&D. This is in sharp contrast to prior eras in technology, where emerging markets — ones with proven and sustainable business models — catalyzed venture returns. All of this has implications for founders and investors alike. If being an early participant in a breakout technological shift is a necessary condition for large outcomes and significant impact, we might be heading to another lost decade.

Where Are The Next Big Waves - Dino Becirovic

Dino’s post is very well-researched and points to this idea that value capture on the investor side must not be predicated on being an early participant to a shift, which I somewhat agree with. That said, I disagree with the premise of this leading to a decade of lost innovation.

Venture has become a far more efficient asset class over the past decade and while innovation in the past 5-8 years has perhaps not seen the same spike as we saw with web and mobile it feels like the incubation period of a lot progress means we are on the precipice of a ton of huge shifts. A proverbial calm before the storm.

What this means as an investor is the same thing as I wrote years ago, that if you’re not too early, you’re late. You’re not only late because you missed this wave, but also because from a competitive positioning perspective, you are behind and forced to FOMO into rounds at ever-escalating prices. It means that once things become obvious, returns compress materially.

However, within these certain areas it also means that the danger of poor execution (as a founder or investor) instead comes down to how you analyze and hypothesize the sequencing of events in the futures you believe in. Looking at something like AI specifically, perhaps the most dangerous thing an AI investor (or founder) can do today is incorrectly project the timescale of progress.

As we’ve seen, many in AI over-projected the development pace and proper value accrual to startups (versus large cloud providers) from 2015-2019 and under-projected the development pace from 2020 to 6-8 weeks ago. My gut tells me that this was due to the technical nature of many of the AI-centric products of 2015-2019 that led to fairly engineering-centric implementations of underwhelming ROI products and APIs.

As AI company creation moves heavily to the application layer, this means you have to bet on both the industry and the company.

On the industry side, you have to project the progress of the underlying infrastructure (the model layer whether that ranges from OpenAI to Academia).

On the company level, you have to understand:

Engineering’s ability to build a malleable back-end, generate a data flywheel, and fine-tune a model(s)

Product’s ability to incorporate and scale these loops that build a short to medium-term moat

The customer sets willingness to adopt AI tools

And lastly, the competition’s competency in all of the above and their strategic view on moat building

Ok so, you basically need to do what a lot of other technology companies do, but in an industry that is moving at breakneck pace and feels incredibly high stakes because this is the moment.

Right?

If today is the moment, how you think about deploying capital as an investor or a founder materially changes versus if you believe the moment comes in 5 years (or even 3 years because venture capital is a hell of a drug that means you need to raise in that time period).

Do you wait to scale up your research team? What do you open-source? How aggressively do you keep prices artificially low? When does the pricing model change? How sophisticated does the product need to be from a UI/UX perspective?

There are a million questions that relate to your hypothesis on timing of the moment and how founders and investors must navigate their views on company building.

Endurance, Crypto, & Market Timing

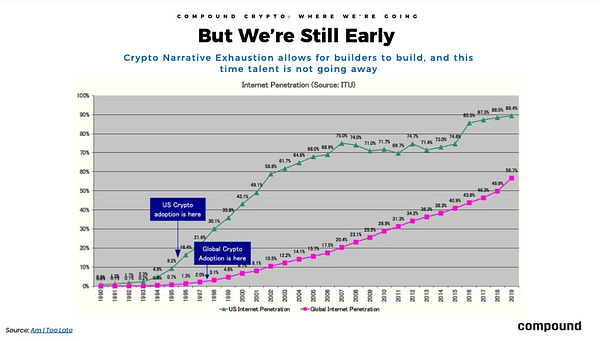

We can perhaps look at another space near and dear to my heart, and one that is the only other category that took us all by storm in the past few years1 which is crypto.

To understand the installation phase of crypto was to invest early in L1s like Bitcoin, Ethereum and Solana, infrastructure like Chainlink, Filecoin, and The Graph, and adjacent centralized enablers like Coinbase, Opensea, and FTX.2

As it became clearer that 2020-2022 was a moment but not the moment, some investors sold with the belief that cycles kill crypto assets. Others have now since realized that the moment will need to be enabled by progress on the builder side (financed by investors) leading to better applications with less engineering-centric implementations of underwhelming ROI products and APIs.

Sound familiar?

Now, deep in the trough of disillusionment with a variety of regulatory and macro headwinds, the question for investors and builders is understanding the endurance of existing projects to emerge out the other end of the bear market and capture value of the next moment.

But endurance is a funny thing in these types of areas, especially with today’s transient talent markets, and an asset class (VC) that is woefully addicted to the New Shiny Thing instead of the incumbent enduring asset. Because it means that you have to understand even short-term psychological dynamics in these spaces that you’re getting to too early.

First Mover Advantage?

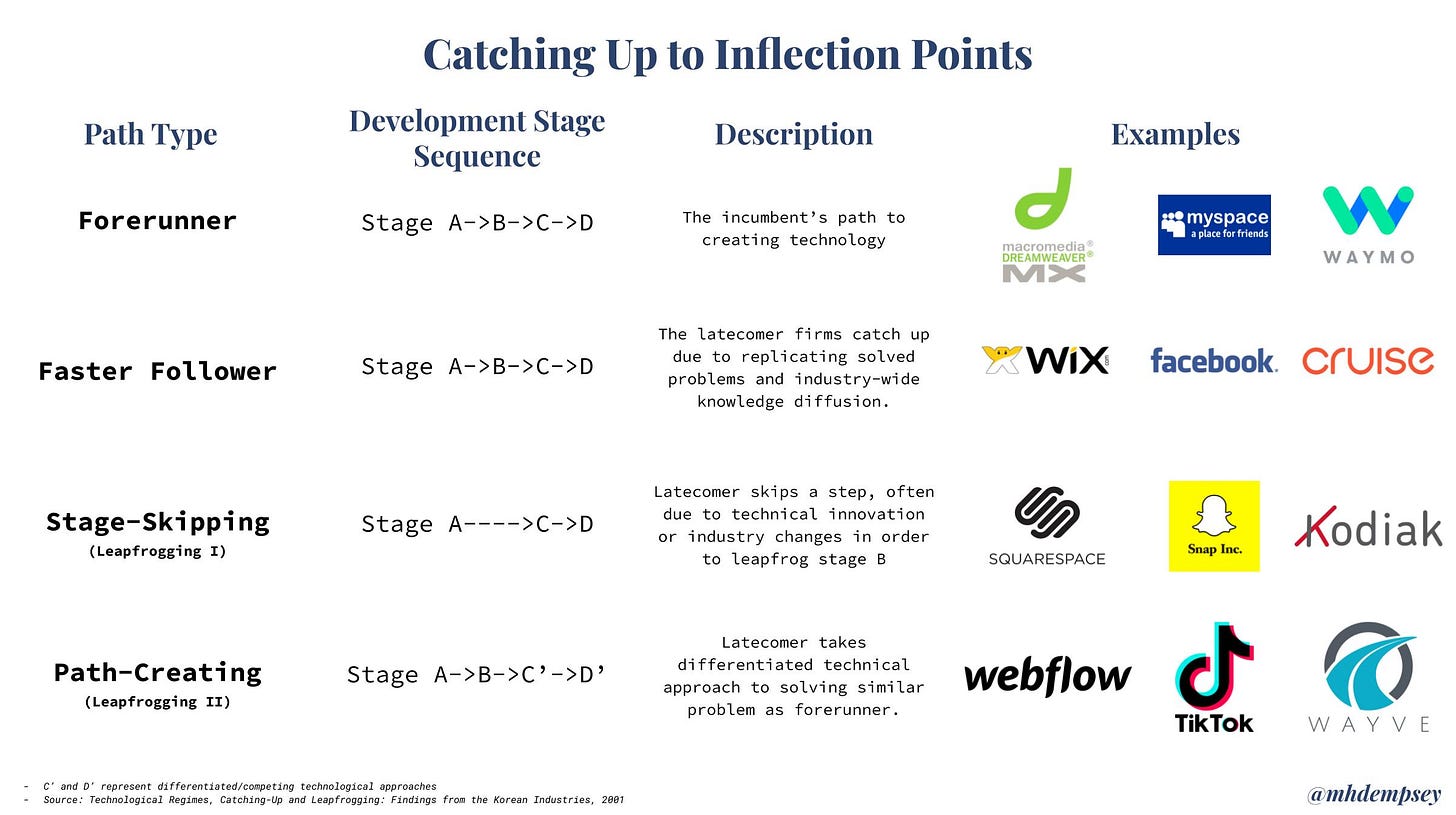

Want to know how to lose a little bit of money? Invest in a company that is too early for a category.

Want to know how to lose a lot of money? Invest repeatedly at escalating prices in a first mover company that captures the early heat of commercialization only to be lapped by a second or final mover advantaged player.

Is this what will happen with AI? Will all of these first-mover companies built on top of GPT-3 or other models with simple but high ROI products rise and fall?

Close your eyes and imagine this: You’ve been early to The Market, you recognize that this is The Moment, and you back a first-mover that captures the space because they are the best company at that time. They are executing on the promise of the market, they are scaling rapidly, and articles are being written about how this new technology will lead to bigger outcomes than anyone ever imagined in the space.

It’s great right? You are god’s gift to the investing world.

Now imagine a revenue chart that looks like this:

You just lost a lot of money.

The Most Dangerous Thing

So earlier on when I wrote that the most dangerous thing an AI/ML investor or founder can do today is incorrectly project the timescale of progress, I lied.

Perhaps the real lesson in all of this has been that over the past few years, as these waves built, capital was deployed into ripples (not waves) of innovation in a way that turned venture capital into execution capital with limited downside variables that were fairly known.

Now, these waves are building against a backdrop of a disastrous macro environment and investing is once again a hard and complex business with a larger and more competitive set of investors begging for a new narrative, and founders searching for a new mission than ever before.

So with this all in mind, the actual most dangerous thing an AI/ML investor or founder can do today is mistime progress, misunderstand value accrual, and get trapped by false product-market fit caused more by the ROI of the technology than the ROI of the product.

Or maybe if that happens you just were too early.

I would argue computational biology should have, and let’s just ignore enterprise SaaS

Disclosure: Compound is an investor in The Graph and Ethereum