A Thousand Ways

On the story we keep telling for our entire life

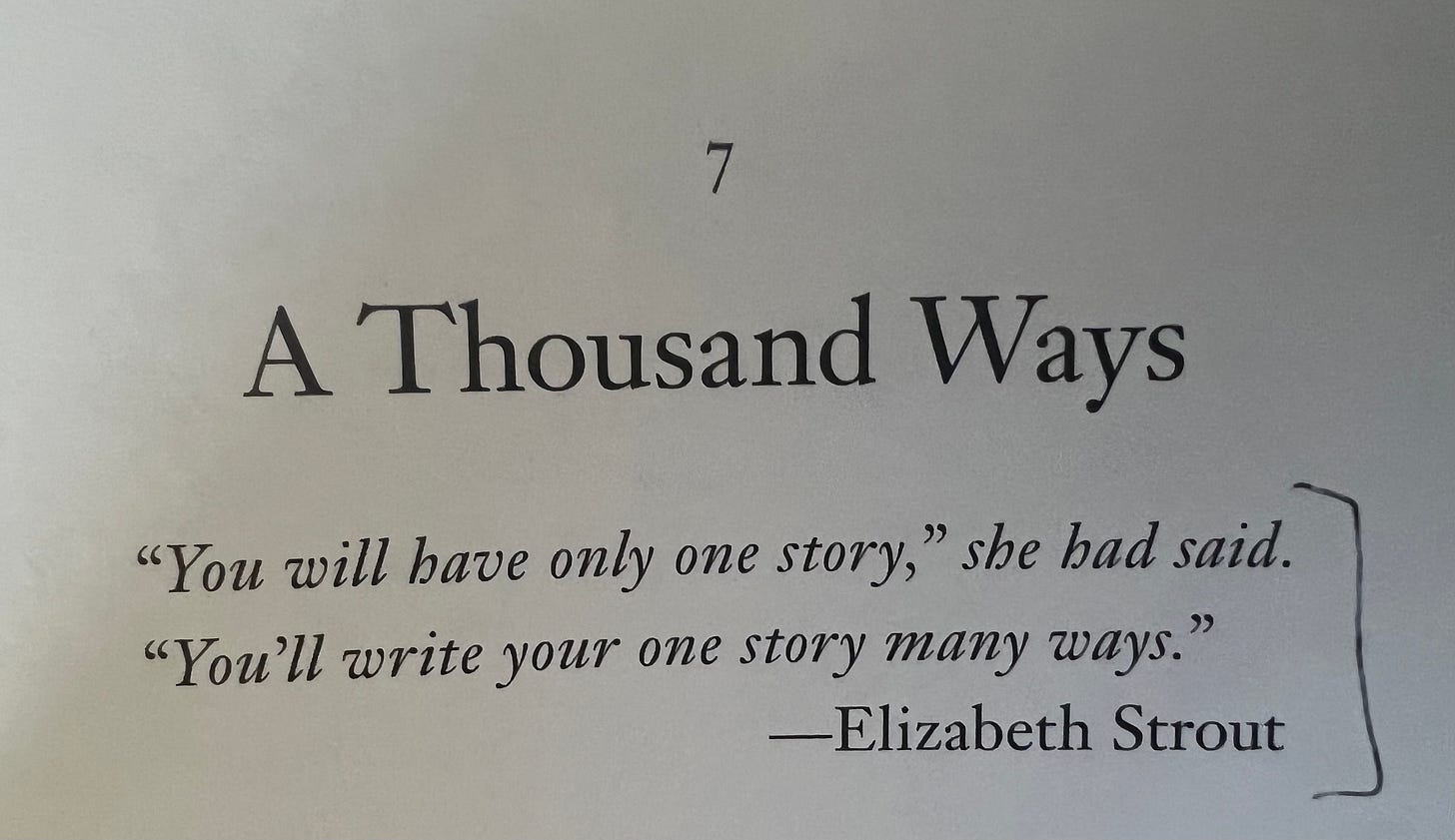

Sally Mann’s seventh chapter in her latest book Art Work is titled “A Thousand Ways.” She leads with a quote from Elizabeth Strout you can see above.

I woke up this morning, the first morning of 2026, wanting to write about writing.

This strange desire, because too many people write about writing, comes at a time in which I have put words to paper more over the past few weeks than any other time in my life. I often find these sparks of inspiration come from decompressing, introspecting, and sometimes from reading something that rearranges a variety of things in your worldview that you thought you knew or understood.

Words that make you smile as you repeat them out loud. Ideas that pain you to just be internalizing now.

I’ve been fortunate enough to have that happen multiple times recently and since we’re not quite done reading Brené Brown, I’ll point instead to Sally’s jarring (for me) statement from her book:

“Regardless of our medium, we all tell our own story, the story we care about and the only story we can tell with conviction and passion. We tell it over and over again, and the proof of a successful creative career is how inventive and complex our variations on that story can be.”

I think this is one of the most important paragraphs I read in 2025 and perhaps in the past decade.

I read it a few weeks after I wrote The Luxury of Knowing, which circles a slightly adjacent idea: how lucky we can be to find our place in work life. Perhaps, in Sally’s framing, to find our story.

I have since shared the quote and concept of our Only Story with a few friends who all went on to ask what my story is.1

I’ve been trying to answer that question. Watching and hearing the words arrange and rearrange themselves as they pass from my brain and into text messages and conversations, all taking on variations that are probably not quite complex enough.

The closest I’ve gotten, after a few attempts and a lifetime of wondering, is that I think my story is perhaps about writing itself. Or at least, what writing does in order to allow us to find what we’re looking for in connection, people, our lives, and the world.

The act of reaching into the complexity of our heads, chests, hearts, and guts, finding something formless there, and pulling it out into language. Giving it edges. Making it clearer than it was before, even if only slightly. And then, if we’re lucky, being able to hand it to someone else.

Sometimes we do this publicly, both for strangers who eventually become familiar and for people to hopefully find some latent connection with the ideas. Tapping a tuning fork and seeing who resonates.

Sometimes we hand this writing off privately, in letters or notes that loved ones can see us in, can return to, can read again when we’re not there to say it ourself.

Sometimes it’s just for us, alone at a desk, trying to understand what we actually think or feel about the world.

The page as a mirror. Words as microscopes to peer deeper.

This is what I do when I write about the future, when I think about how technology or science is cascading through the world. I read. I listen. I have conversations with people smarter than me and catch glimpses of something taking form at the edge of my vision.

Permutations and possibilities of futures we might believe in and people we might see coming from a decade away.

And then sometimes I take the leap by committing to a version of what one thinks they see, putting it on the page with enough edges so that someone else might see or feel it too.

And this is what I do, or what I’m trying to learn to do, when I write for the people most important to me. Allowing words to give shape to the things I’ve been wondering about, carrying, hoping for, struggling with, and creating surface area for others to do the same.

But there can be tension in relying on writing too much or attempting perfect prose.

I used to think sharing what’s going on in our head’s was about precision. Finding the exact right words, the cleanest possible expression of an idea.2

I’ve come to understand that clarity, the real kind, has little to do with precision. It has to do with honesty in its most unguarded form.3

Precision feels good, because it creates a false sense of security. You can spend hours finding the exact right word and never once risk being seen. A perfect sentence that despite having all of the right words, actually reveals nothing.

The harder work is writing that feels like it has stakes. Saying the thing you haven’t said, not because you couldn’t find the words, but because finding them meant you’d have to face them and/or put your thoughts into the world for all eternity.4

This is why I always say that I wish my friends wrote more. I want to know what they circle back to. What sits in their chest. What won't leave them alone. It's perhaps why so many of us enjoy long walks. Something about the monotony of it lets people slip into idea spaces they usually don’t explore. You walk long enough and eventually someone says the thing that’s been bouncing around inside of them for days/months/years. A version of their Only Story.

Maybe a perfect sentence is actually one that wanders throughout our minds, out loud.

A few close friends and I had an end of year dinner a few days ago. We shared a few questions that we wanted to reflect on going into the new year, and on that printed piece of paper was the quote which asked each of them to share what their stories were.

What is the thing they are trying to make sense of, to tell over and over again?

Watching them sit with the question, watching them reach for something true rather than something easy, was a highlight of the year.

What I keep returning to, what feels like a small miracle, is that Sally (and Elizabeth Strout) saw this at all. That the story we tell over and over again, in all its inventive and complex variations, doesn’t stay in one silo. It moves through everything. Through the work and the love and the deep conversations and the things we write when no one is watching and even to the small investment firms we build over a decade.

The same story, just on different pages. Finding its way out however it can.

Some because they genuinely wanted to know. Others, I suspect, because they were tired of me sending them another quote I’d fallen in love with and felt obligated to engage.

When I was 29 I wrote “I feel like each year that goes by I’m writing a cliche about a boy growing up into a man and figuring out how the world works, while every adult could have told me this over and over again.” Feels apt to surface that here.

Some might call this vulnerability so I guess we did get Brene Brown in here.

The internet isn't written in pencil, Mark. It's written in ink.